This shows the door to my home working room. My work explores my psychological reactions and adaptation to WFH through staged dioramas of my emptied consulting space. It is a reflexive investigation, using vernacular, medical, and other objects ordered from ‘Amazon.’ A year after taking the original images (April 2022) I photographed folded 3-D printed images of my work. The folding and shaping emphasises the material and immaterial aspects of my work by the multiplication and layering of space, objects, shadows and meaning. My experiences connect my story to wider social and cultural understandings about working from home.

This is my medical bag. It remained in my hall for 9 months as I worked from home. A reminder of what was lost for a time.

I found the change from workplace to working from home difficult. Sometimes I was in a fog of uncertainty about my contribution and identity as a doctor.

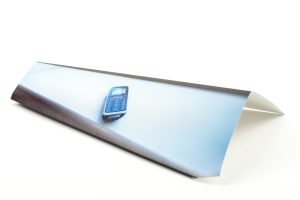

My phone is not a substitute for the personal contact that I am miss.

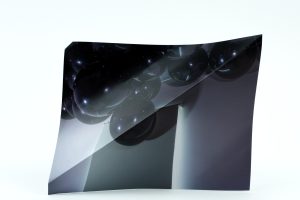

For several months I slept poorly and stumbled from my bedroom to my consulting room to have another day with my phone, thinking that I wasn't doing enough for the company. My work explores my psychological reactions to WFH through staged dioramas of my emptied consulting space. It is a reflexive investigation, using vernacular, medical, and other objects ordered from ‘Amazon.’ A year after taking the original images (April 2022) I photographed folded 3-D printed images of my work. The folding and shaping emphasises the material and immaterial aspects of my work by the multiplication and layering of space, objects, shadows and meaning. My experiences connect my story to wider social and cultural understandings about working from home.

Sometimes I wanted to show my anger about working from home and feelings of being neglected. I started to smash things up in my consulting room and garage.

There is a heaviness that hangs in the air sometimes when working from home. It's those down days and weeks of torpor and low mood and negative thinking about not doing quite enough from home.

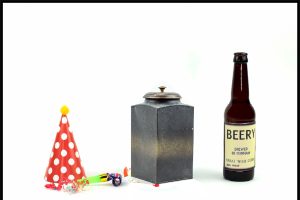

This was taken on an evening when the UK remembered all the people that had died in the Covid-pandemic.

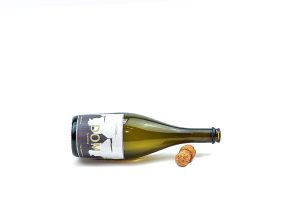

One of the ways that I coped was to drink too much to reduce my anxiety and try and help sleep. These are the bottles from my neighbours - perhaps we shared this displacement activity as well as our neighbourliness?

They say that Covid is 'over.' Maybe that's the case for photo editors and politicians, but I still talk to patients about family deaths and disordered lives.

Hoarding pasta and Amazon deliveries are part of our experience of lockdown.

This is the head of my kitchen mop. It brings to mind a person. In this conceptual work, I connect with my feelings and concerns about how the COVID -19 pandemic has been managed. It is a reflexive investigation, using vernacular objects and medical paraphernalia, to create still life assemblages that are serious and playful. They mark the ‘ordinary’ pandemic events of ‘Amazon’ deliveries, bulk buying pasta, and working from home in extraordinary times. Collectively they challenge dominant medical and government readings of the COVID -19 pandemic, such as 'Partygate' and a huge death toll.

My personal views connect my story to wider social and cultural understandings of the pandemic. At their extremes, they are either supportive or critical of the UK pandemic response. My assembled scenes make us question whether we have been ‘following the science?’

This assemblage is a homage to Man Ray's assemblage Mr Knife and Mrs Fork (1944) and speaks of the prevalence and contagiousness of infection.

"Home used to be a safe place, but it is no longer as I am now working from home" (Quote from a home working GP). Based on May Ray's 1922 artwork 'Cadeaux.'

"Working from home is part of the workforce but you don't really feel that sometimes. You feel anonymous."

I am a doctor that has felt that strain alongside my colleagues working face to face with patients or from home. This is my stethoscope and my wife's stethescope.

It came to a head in a 'private' corridor while most people were social distancing.

This is an improbable tale of driving blind in Barnard Castle.

The BBC's covid briefings signify myths about war successes and institutional power.

The heart of the matter of Partygate is that politicians partied when the public adhered to their advice and saw their loved ones die at a distance.