Artist and photographer Ky Lewis has been wowing audiences with her ethernal lumen prints and recently exhibited at the Shutter Hub OPEN, creating further interest and dialogue about her work, and life and death. We caught up with her to find out more…

Who are you?

My name is Ky Lewis, I live in glorious South London and have done for many years now I suppose I think of myself as an artist and photographer, I don’t like to pigeonhole myself as I love all processes and methods of working. I studied Graphics, then moved on to illustration and printmaking and throughout all of this the camera was a constant. I worked freelance after college doing illustration which involved mostly printmaking techniques. These days I run an education group and I do workshops whilst also trying to continue with my own interests. My current practice mostly centres around camera-less work and has done for a good few years now, though I love making pinholes using recycled cans and the like. These have become the core of my practice.

When did you first discover your interest in photography? Also when did you become interested in alternative processes specifically?

I was given my first camera at the age of 13, a Praktica TL, I loved it, it weighed a ton and felt good in my hands. I used that until it wore out, much like my second camera a Pentax ME Super which I had for years I would go for bicycle rides with it and capture the local creaks and cliffs. My interest in alternative processes probably came from my printmaking background, I think this approach to photography means I can explore those processes using both media.

Where did it go from there?

I studied many courses and for some years, loved being a student and having all that access to equipment, my last uni was Camberwell School of Arts and Crafts, it is now called a college and part of the homogenised group that has become UAL in London.

Whilst still studying I was offered a dream job of choosing my own book to illustrate and this was part of a private press called the Inky Parrot Press. Hogarth’s Peregrination, was the first book I really loved illustrating. I had made bookcovers for various publishers but any photo refernce I used was only to inform at that stage and it wasn’t actually used in it’s own right.

These days I often work in a camera-less way. It feels more like painting than photography, even though I use light and silver gelatine or I’ll sensitise my own papers, it seems strange not to use cameras as much. I still do of course and I always carry something with me, such as my Zero Pinhole or a small compact point and shoot.

What was your first job?

My first job, other than the standard Saturday fling for a newsagent or supermarket and a brief stint at a local ferry company, was probably really small, I was a self employed illustrator and I worked on lots of jobs that involved supplying parts to a larger piece. I had worked for the British Tourist Authority, Countryside Commission, various publishers like Bodley Head and small private presses such as Hanborough Books and New Arcadian Journal. I sold prints of work and took commissions for one off pieces of painting and illustration.

How did you get from your first job, to where you are now?

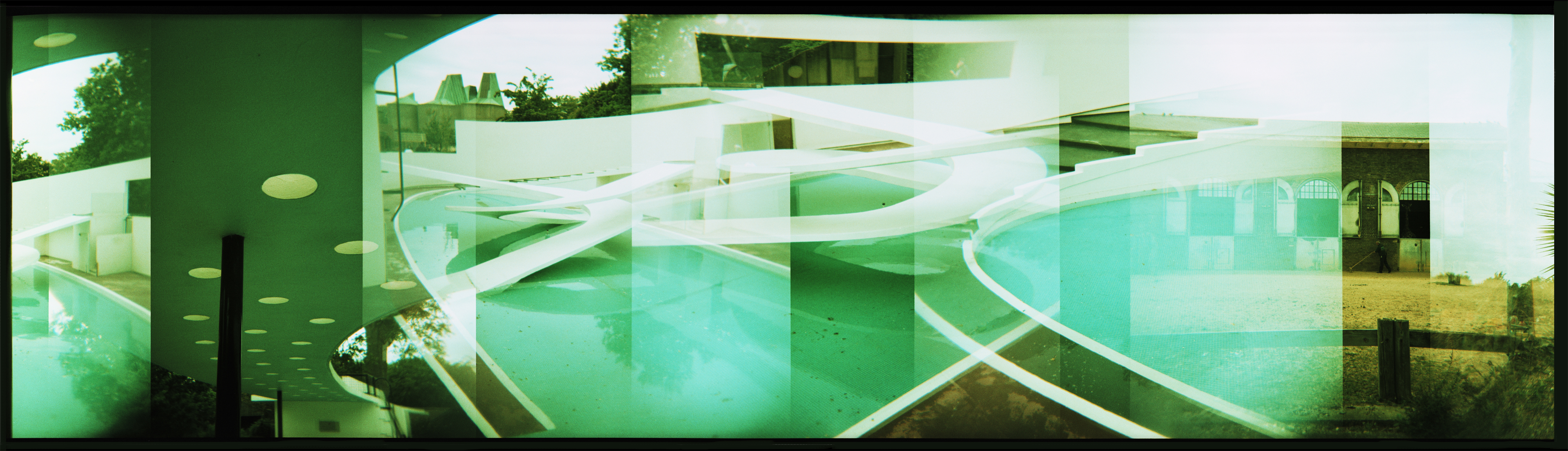

After all those smaller jobs and then doing some rather large projects with stressy deadlines I stopped for a while and brought up three girls, always making images for myself during this period just to keep my hand in. I started to concentrate more on photography and instead of using it to inform engravings, lino cuts and other illustrations it became it’s own work. My Pentax after it expired was replaced with a Canon and that is what I used for many years but I would play around with the lenses and not do straight prints in the darkroom. I acquired some Toy cameras and the Holga bacame my go to camera, always in my bag and loving the lack of control I started to stretch it’s square format and would create panoramics that would fill the 120 film. I was having a lot of fun with cameras such as the Supersampler as well and I loved the sense of motion within the frame. Strangely these led me to pinhole cameras and capturing the multiple moments on film, not just that micro second but often minutes. This has expanded into months and years with some of the solargrahs and days when I create my camera-less images as Lumen prints.

I am curently Artist in Residence at Stave Hill Ecology Park in Rotherhithe, London. This has given me the opportunity to explore making documentation of the site with both pinholes and camera-less work. The cyanotypes, lumens and anthotypes will record the plants across the seasons and capture the natural beauty of the place, whilst the solargraphs and pinholes both do the same but are also used to record the many events happening at the SHED – which brings people to the site to look at a range of subjects from Soundcamp in May to the Oral History event and insect and plant days, giving people the chance to engage with nature and their local surroundings. I seem to have fallen into this type of work and it suits me as I love working outside and enjoy working with people sharing techniques in workshops and recording them in unusual ways. It takes a while doing pinhole portraits with available light! It seems all the work is rather long on the exposure side.

Our recent ‘Do You Like Love?’ exhibition included your Lumen print ‘Dying Light I’. Can you give us some insight into the background of how the work came about, and your relationship to it?

‘Dying light’ (opening image, above) was a response to the ongoing work I was doing exploring the nature of death and decay, the series had slowly got bigger – literally the scale of subject had grown from my initial interest in insects trapped, caught on paper and immortalised as Lumen prints, an essence of themselves, an imprint captured like a photograph from a microscope. With each successive piece the subject got bigger, the exploration of the minutiae of death became more interesting when other elements would be introduced as the subject decayed. It was then the marks that these left, the trails and the stories as the work developed that became the focus. The insects would be brief, a quick capture, much like there lives very short and ephemeral. Rodents followed then a cat was offered, how could I refuse, it took a strong stomach initally but then the road kill kept coming my way. The deer was beautiful, it looked asleep and unharmed, it was not easy to work with and I tried to be respectful. I wanted to capture the essence of the animal. The first couple of prints from such subjects always glow but it really is like the life leaves and the images change. This is when there is a transition and new life is evident, it doesn’t really take very long. The marks that are made are often beautiful and if enlarged capture aspects of the surface that you wouldn’t expect. It is a very visceral process initially, very physical and invasive. I have to be clear in how I want to place the subject, not always easy on such a large scale. I will sometimes draw the subject whilst it is decaying, I do take documentation photos but it is more about the final image on the paper for me. There are often a series of images and sometimes I get it wrong and the emulsion is also consumed much like the body. This leaves an empty space but that can be just as important.

I was lucky to get the deer, I do not expect to have that chance again any time soon. I have since made lumen prints with squirrels, mice, birds of many sizes, sea creatues and fish.

Previously collections of your work (‘Wide Open’ and ‘Pinhole & Plastic’) have centred on images created with pinhole cameras made out of discarded or disposable items (old tins, boxes, etc) and ‘toy’ plastic cameras. What is it about the process of using such items that inspires you?

I think the limitations associated with using ‘toy cameras’ actually gives you a freedom that you don’t get with over-specced cameras. You have maybe only two choices, sometimes none and because of that you really look at what you are creating in camera. I feel a sense of space and a reduction in distractions. I just have to know how that film may respond in certain conditions and then it is all about the composition. I was taught, many years ago by Maureen Paley and Niall Doon Connelly that you compose in camera and only click that shutter if it moves you, it has to be a gut approach for me. That has always stayed with me.

Pinhole cameras are a joy to use, wether bought or made, it is that passage of time which I love, it is not just a split second caught but many seconds, many moments. I prefer having evidence of movement in the pictures and I’m really not fussed about them being ‘sharp’ I love making my own cameras and the first I made, other than the ubiquitous shoe box was a cylindrical camera made from a cashew nut can. It shot film and meant I could do a whole roll, I love the results, drawn out panoramas of overlapping subjects, it was a photographic illustration made in camera.

In a world where photographic technology is developing rapidly, how do you see the role of alternative processes? And do you see an increased interest in alternative processes as a reaction to the proliferation of new technology?

There is a growing interest in alt practice and like the desire to have vinyl(if you’ve never had it before) I think this comes from the need to have some contact with materials, a tactile connection to your image creation. Hands on craft processes and skills that take you away from a screen. The unexpected, the lack of total control, a serendipitous adventure. I am amazed at the growth in interest for all these processes and I do think it was fuelled initially by the likes of Toy cameras and that look, the unfinished, haphazard vignetted Holga image which then was taken by Hipstamatic and subsumed into the digital world again. So the next thing was to remove the camera and create images as prints that involved working the paper applying your own emulsions and of course then leading us in a circular fashion to using digital negs as part of the process. An abstraction or enlargement or going further still and making your own collodions in camera and that of course taking us right back in the history of photography.

I think that marriage of analogue and digital is impossible to avoid and certainly impossible to ignore especially if you intend to share your work online. It is difficult to do without scanning or photographing it. A vicious circle maybe, ironic really.

Who do you admire?

I have extremely diverse and eclectic tastes I think it is important to feed creativity by looking at all sources of art, design and photography. I don’t think I could ever name just a few influences. I first went to Lacock Abbey when I was 13 and I suppose that exposure to Fox Talbot made a lasting impact, though I didn’t know it at the time. Walker Evans, I found his work fascinating the characters and the documentation of dilapidated homes. Berenice Abbott for her incredible range from architectural to experimental. Artists such as Bacon, Aubach and Baselist. Cocteau, Moriyama, This is very hard, The work of so many of the camera-less photographers obviously has an impact though I was ignorant of many of their practices until recently. I greatly admire the work of many of my contemporaries across the globe and its fantastic to have the chance to see their work develop. Look out for members of the London Alternative Photography Collective and the many world wide members of Shootapalooza.

Where do you see yourself in 10 years time?

There are a number of processes I really want to try and I would hope that I have explored those. I want my studio to be completely finished and I would like to be making works that stretch me as an artist/ photographer and if I’m lucky someone is vaguely interested in looking at it. No matter what, I shall still be making images in some form or other. Maybe with a nice sea view at times!

See Ky’s portfolio here

Is there someone that you’d really like to see us interview on Shutter Hub? Drop us a line and let us know!