Shutter Hub member Wendy Aldiss is interested in people and the human condition/experience. Her work is influenced by the people around her and key stages in life. Her images include the portrayal of people themselves through environmental portraits and the depiction of emotions and experiences.

Following the death of her father Wendy realised that, in a way, she could continue to photograph him – by making images of his possessions. She went on to photograph absolutely everything that he had in 2018, right down to his paperclips. This labour of love and grieving has resulted in a fascinating and complete catalogue of the items owned by a man of 92 years; a writer, poet and artist.

An intriguing collection and insight – My Father’s Things is a story of a life well lived and a man well loved.

My father was hugely important to me. My father died the day after his 92nd birthday. Gone.

After the initial weeks of grieving the realisation grew as to how much I was missing photographing him. Taking photographs has long been a way for me to cope with upset and adversity, as well as to rejoice in people and places.

I began taking photographs of his things and that both kept me near to him and prepared me for the clearing away of his possessions. Over the following nine months I photographed everything that he had left behind at the hour of his death; all his worldly goods. It was quite a journey.

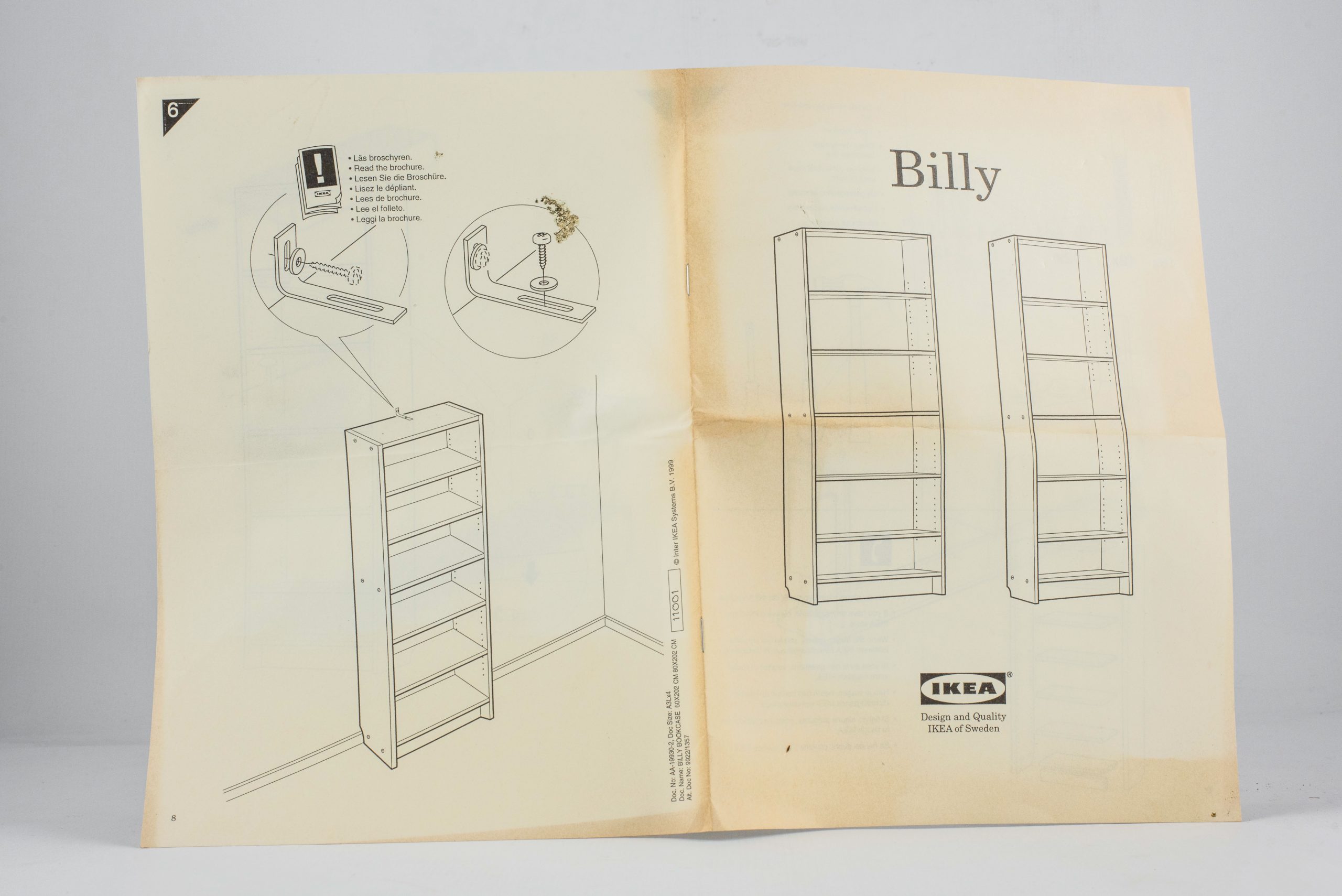

In my exploration of his world I came across things that I had expected to find – e.g. his clothes, birthday cards and many, many books – and other items that were a surprise e.g. notes written to me and my siblings, early paintings and, yes, his ActiumPlus. The resulting photographic series, ‘My Father’s Things’, comprises 9000+ images, many of them surprisingly beautiful.

Although it is a depiction of a single person’s property, this body of work has a universality. Having to sort out the things belonging to one’s deceased loved ones is an experience that touches the lives of many. Separated from their surroundings, these images prompt the viewer to contemplate the intrinsic merits of design and utility in the objects we handle and to consider their own possessions; the importance they have attached to them and what will become of them after their own passing. I am thankful that a unique set of circumstances contributed to the successful completion of my project: my geographical and emotional proximity to my father; enjoying 24 hour access to his house and possessions; having an understanding family; and, although working against the clock, sufficient time to photograph everything. Without these, such a task would have been impossible.

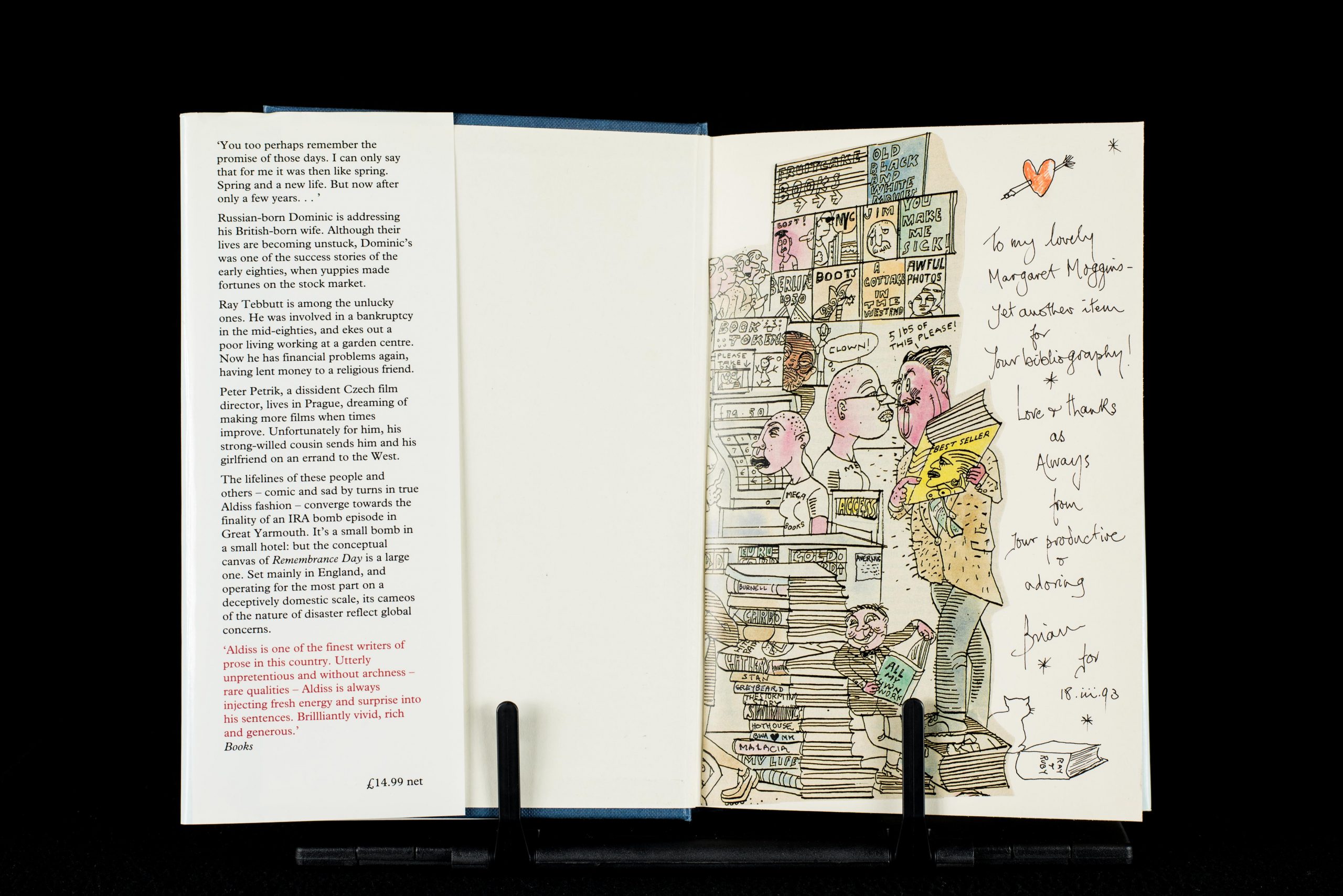

My father had amassed an extensive library; almost every book on the shelves contained pages of particular interest bearing his mark. He owned recordings of music from all over the world and artworks, many his own, filled the walls. Looking at these still life images, there is just as much interest in the everyday objects such as a nailbrush, a pair of shoes, the contents of a desk drawer, as in the more unusual – his literary awards and medals.

It is worth saying a bit about how my Dad would have viewed this documentation. I have total confidence that he would be delighted with it and do not have any qualms about making public any, and all, of his possessions. He did not believe in censorship.

According to the Urban Dictionary ‘Your Dad may also be your Father but your Father may not be your Dad. Your Dad loves you, comforts you, supports you and helps you. Your Dad is someone that you should be able to respect.’

My father was my Dad.

You will find out a bit about him through the images in this piece. You will know that he was very important to me from the very existence of the work.

I could reel off a series of dates – markers in his life – but they are readily available online and in his autobiographical works. My Dad was Brian Aldiss.

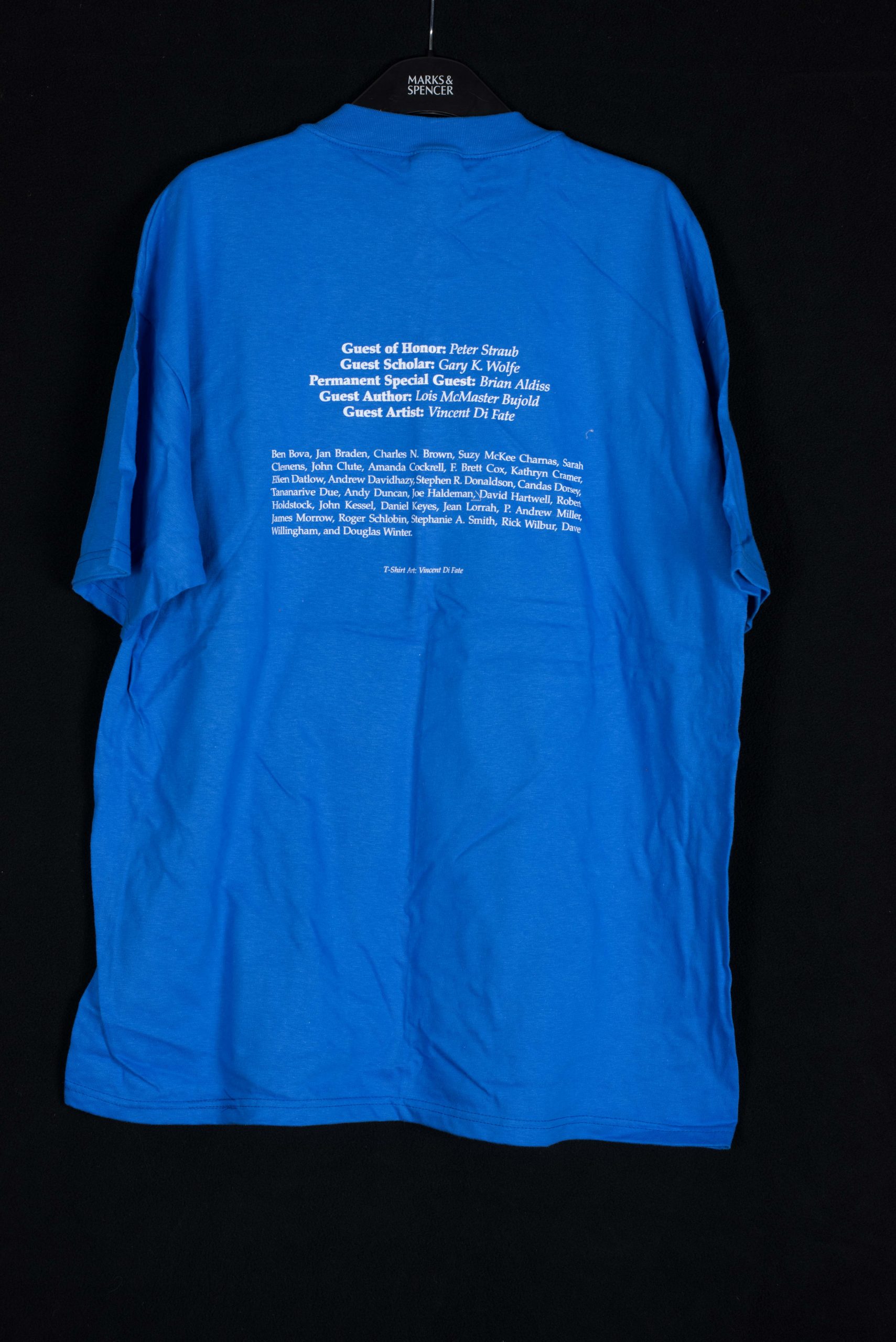

In his own words he was ‘a writing animal’ and writing is how he made his living. What became so much clearer to me while photographing his possessions was how he seemed to manage to fit more into his life that most would in three. As well as writing novels, short stories and collections of poems he was reviewing books, editing story collections, forming societies, keeping up a huge correspondence, quietly supporting and enabling other writers especially those living under oppressive regimes, working on film treatments, gardening, keeping journals, partying, painting, writing and performing plays, attending conventions and presenting papers, collecting stamps, reading prolifically, enjoying music, travelling, running a film club, and, so importantly to me and my siblings, being a Dad. He was married twice, had four children and seven grandchildren and after the death of my Step-Mum had a treasured long-term partner.

Except for the contents of his book room all the photographs were taken in my father’s house and the objects replaced where I had been found them. This kept me in direct contact with my Dad and was important in my grieving. I talked to him a lot of the time and played his music in the background.

Some days the work came easily, at other times it was difficult. Tears would get in the way of seeing if objects were in focus. In addition, I had to photograph in a way I had never done before; lights, photo cubes, backdrops. It was always an adventure – a process of discovery – even just finding cuttings from newspapers such as those on the crisis in former Yugoslavia.

Although I knew he had a wide network of friends across the globe it was only through photographing my father’s books, and reading the tributes inside, that I appreciated how much he had inspired so many others and how friends had remained friends across the decades. I also learned more details about the lead up to his separation and subsequent divorce from my mother which was a less joyful discovery.

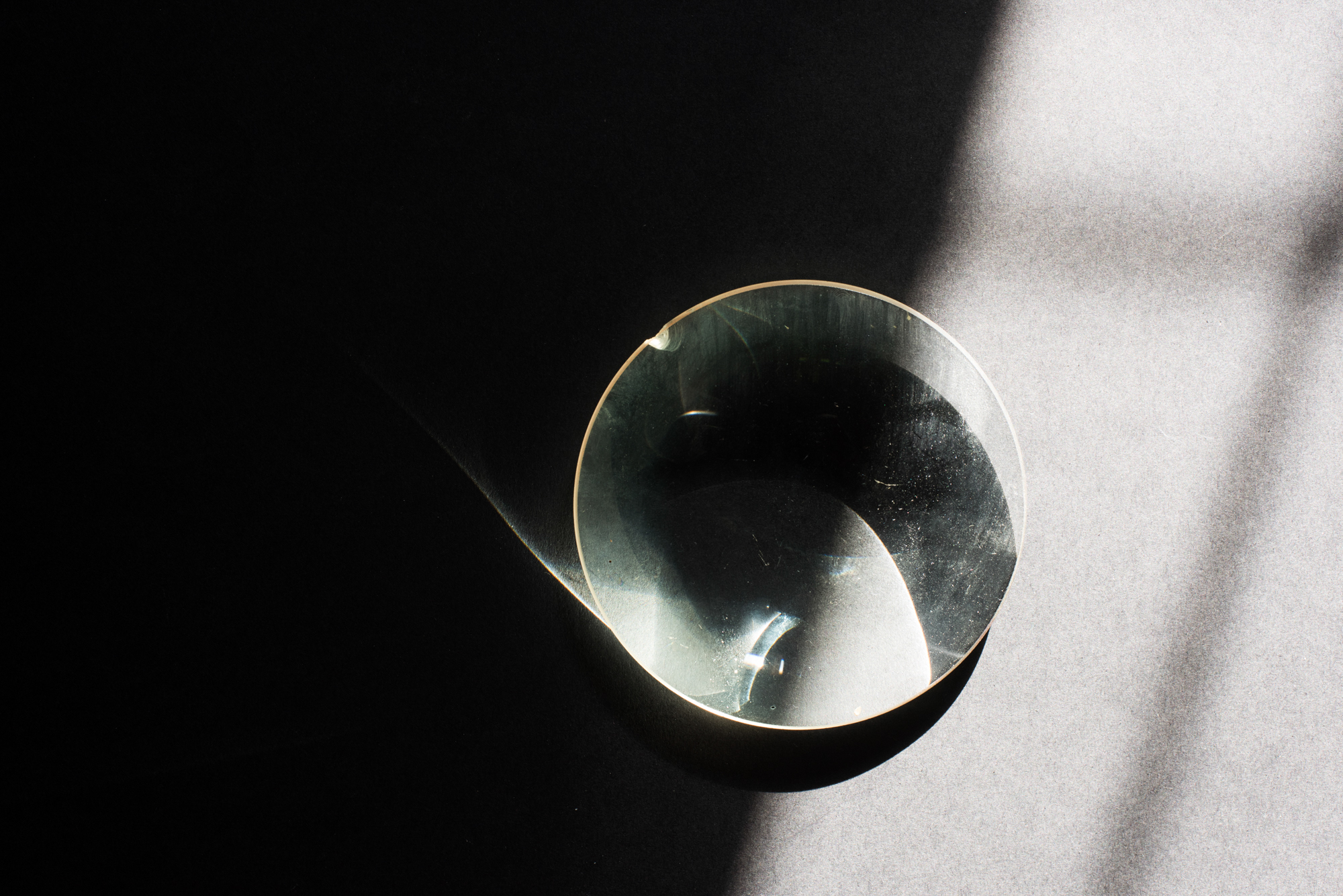

As anticipated, most of his possessions have now gone. Family, of course, have a number of items. There have been a lot of runs to charity shops and re-cycling depots. The hardest things to say goodbye to were the books that we did not have room for ourselves. We hope they find good homes. In the main, having the photographs has helped to dispose of items. The exception has been two kaleidoscopes, which I realised only after reviewing my photographs, were exceptional and each time I see these images I regret the fact that we gave these away. I have kept a number of items which now form part of a limited edition artist’s book.

I am delighted that this project has been so well received by everyone who has seen it and hope that at some point a book will be created so that the images will be seen more widely.