© Josie Purcell

Photographic artist Josie Purcell is based in Cornwall, UK. She has a background covering commercial, portrait and medical photography, while also being a former journalist, and a communications and marketing manager.

While still working full-time, Josie decided to return to her photographic roots and successfully Crowdfunded to support a part-time participatory photography project and Cornwall’s first alternative photography ‘mini-festival’ in 2014.

To reignite her own practice in historic and alternative photographic processes, in 2016 she enrolled as one of the first students studying via Falmouth University’s Flexible MA in Photography. She gained a distinction in this in September 2018.

Josie has been nominated in the Royal Photographic Society’s Hundred Heroines; shortlisted for the Eden Project/FoAM Residency: Invisible Worlds (2018); commissioned by Cornwall Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty and the University of Exeter’s Environment and Sustainability Institute for the 6000 Flowers-Farm For AONBees project; taken part in Garden Leave, a visual artists’ residency at Hestercombe Gardens, Somerset, to help develop an arts centre; and has made a film for Cornwall Crafts Association and the National Trust’s WWI commemorative exhibition as part of 14-18 Now.

An image from her series Harena Now was selected as part of Shutter Hub’s OPEN 2018.

She is now working on a pilot project to bring national and international photographic art to Cornwall, including the potential to create a photographic festival within this.

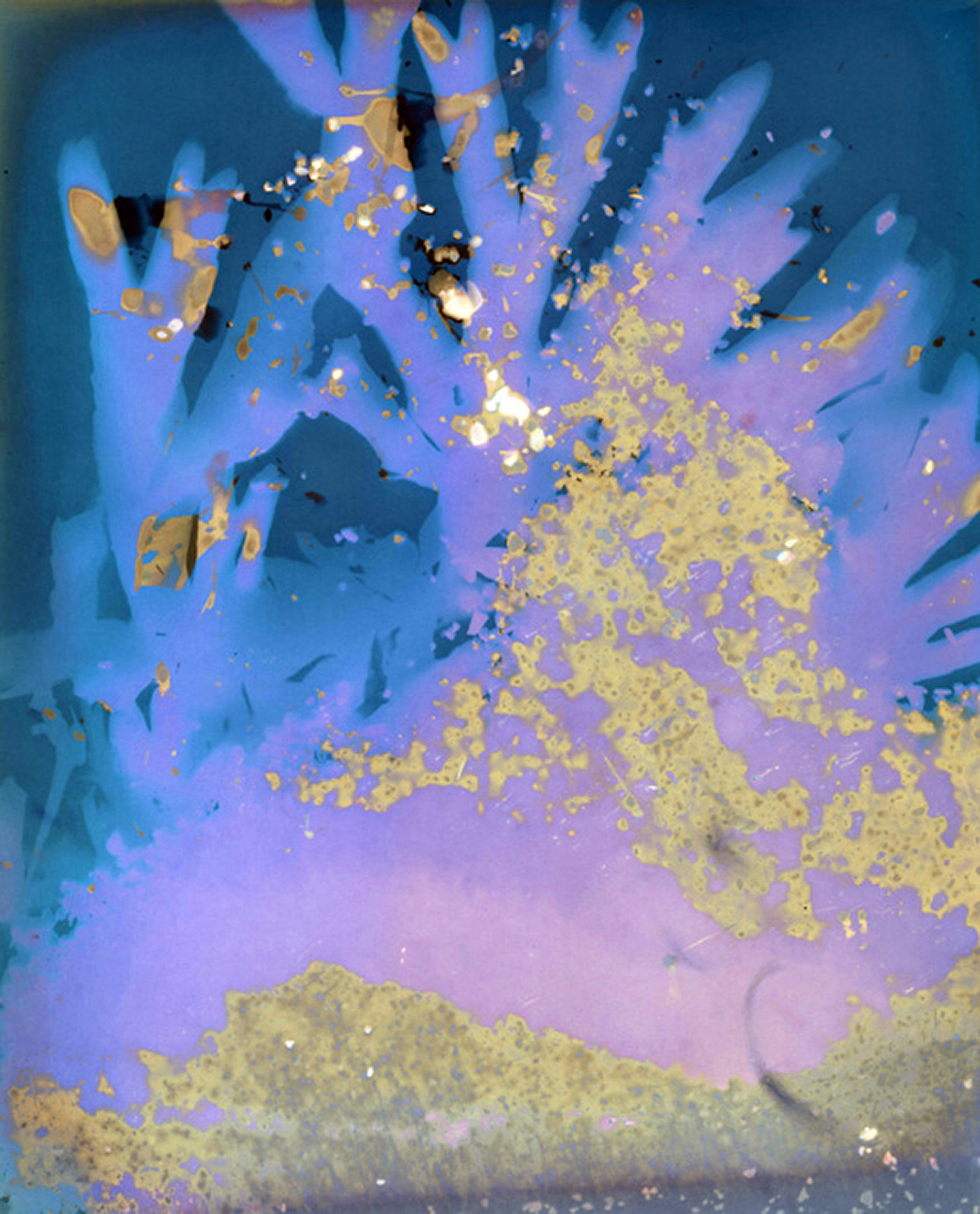

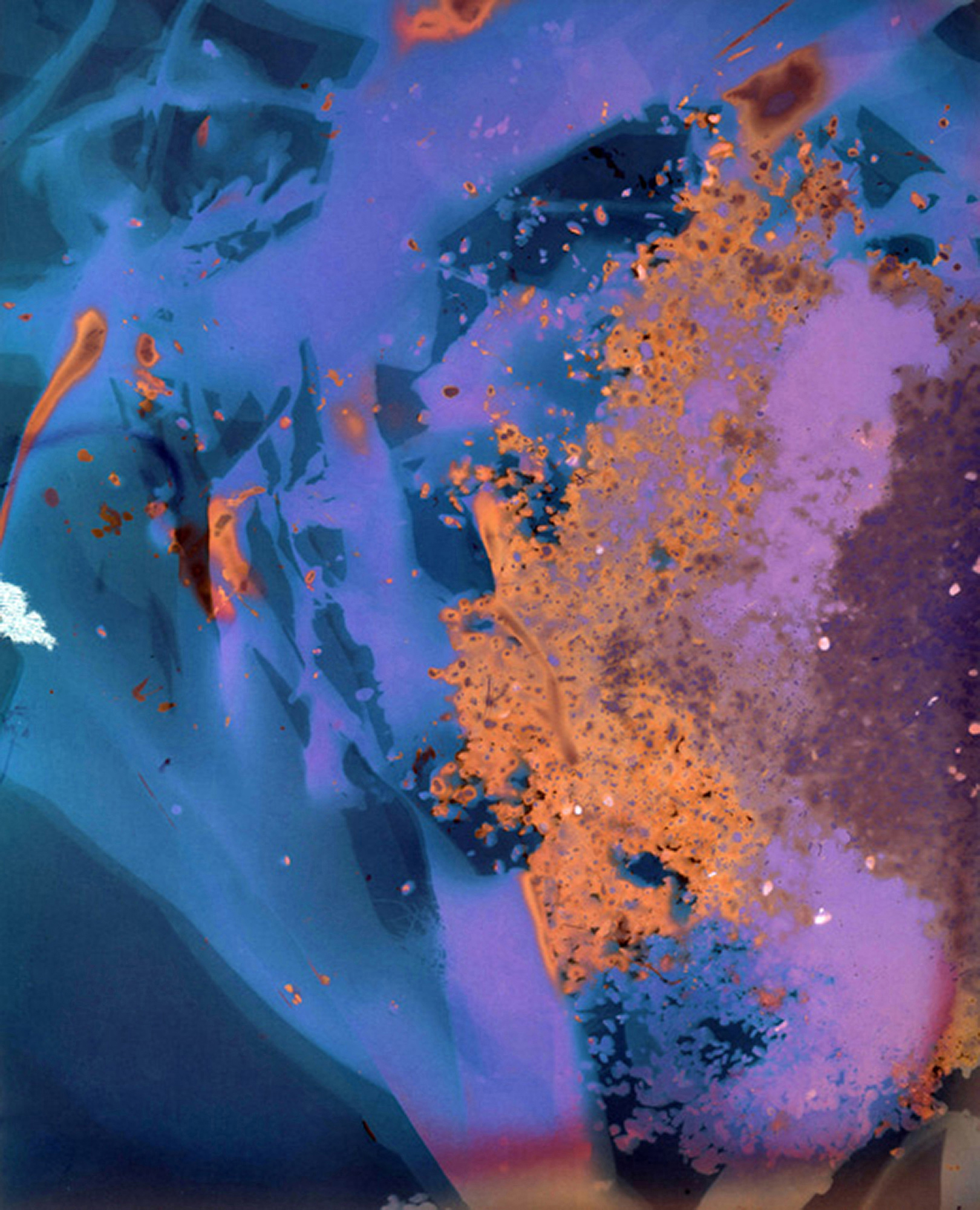

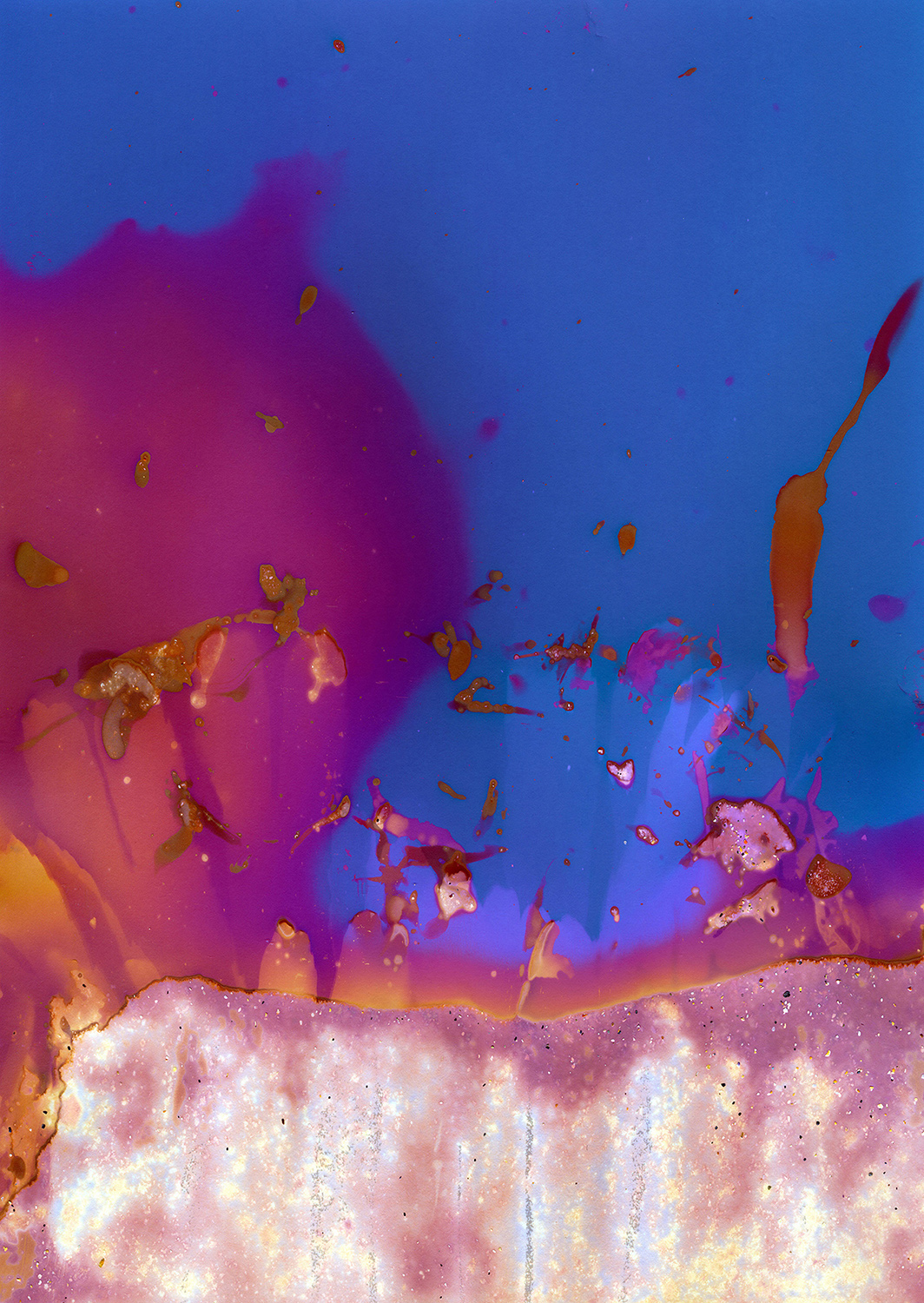

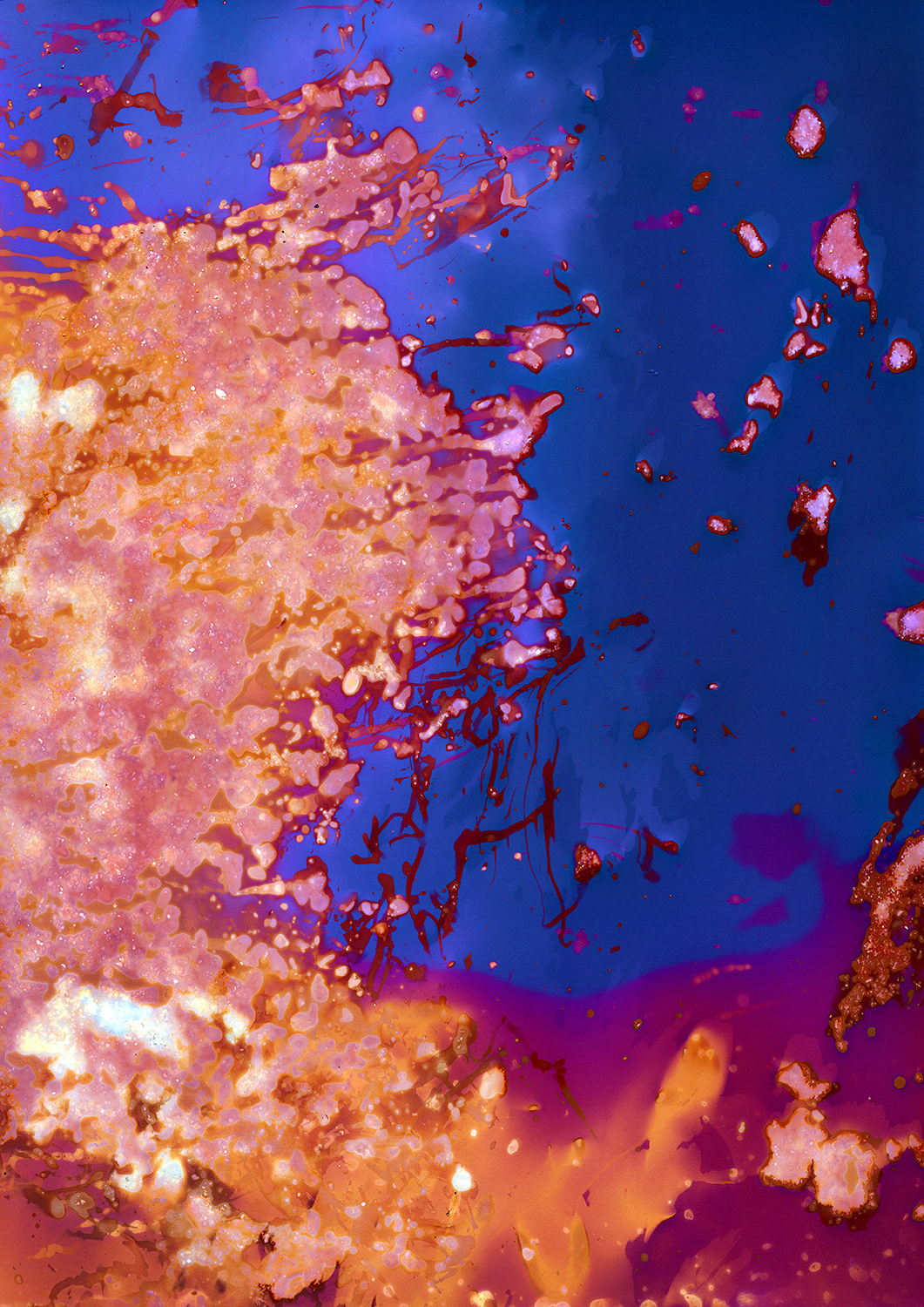

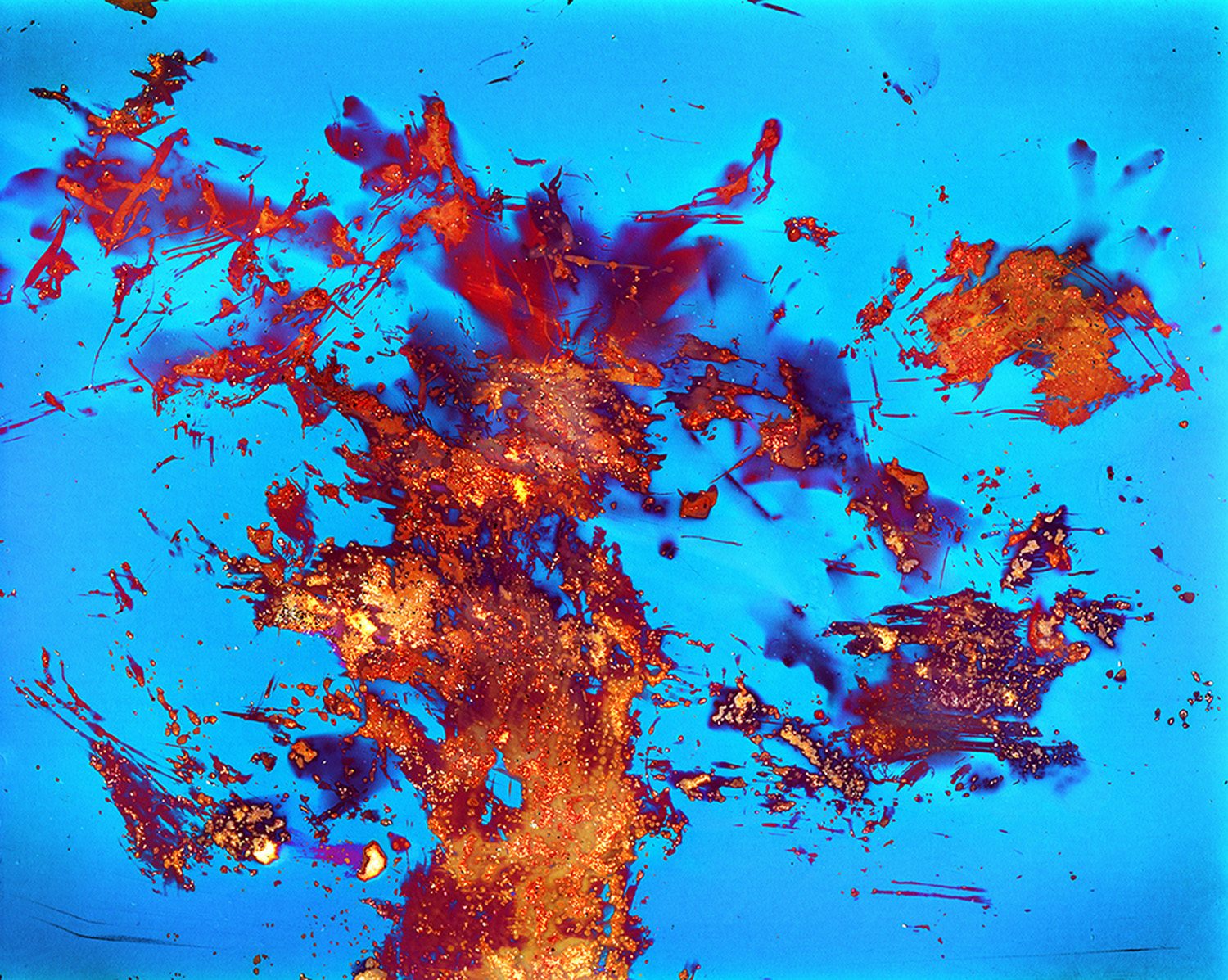

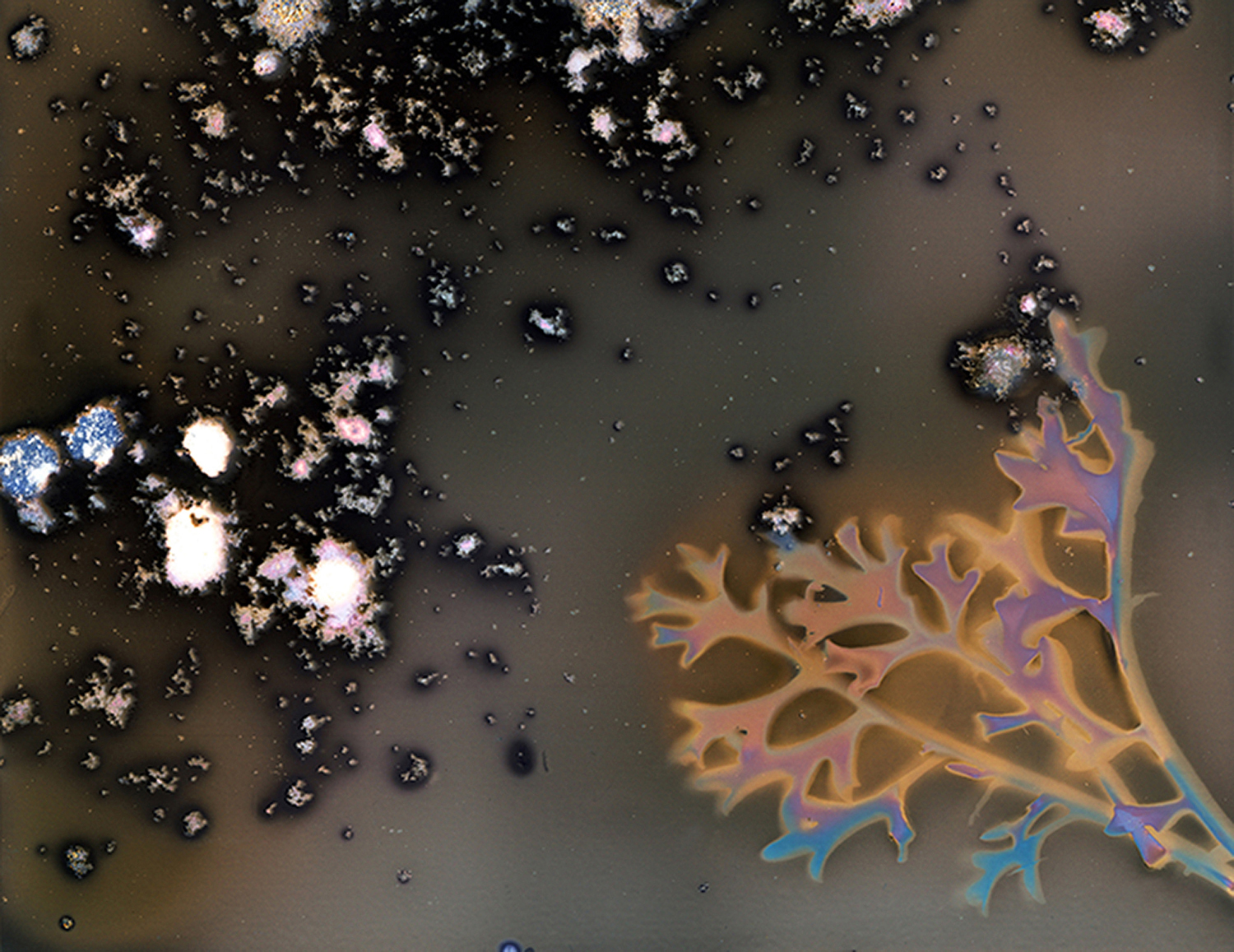

HARENA NOW:

My practice predominantly uses alternative and/or historic photographic processes to address topics relating to the human impact on the natural world.

I tend to use non-figurative images, plumping instead for creating abstract, camera-less images to intrigue the viewer and in turn make them seek out answers.

Harena Now grew from research I undertook in 2017 as part of my MA in Photography. I had initially been working on my Nature’s Goddesses series, which response to our use of plastic. But I felt that given the amazing photographic work being produced by the likes of Mandy Barker on that subject, and the way it had been propelled into public consciousness through the Blue Planet II series, that maybe my photographic voice would get lost, or not be able to add anything more.

I was also feeling frustrated with mainstream news coverage at the time and switched over to watch Al Jazeera News. They were running a piece about the sand crisis.

Living in a coastal location and being able to nip down to my local beaches whenever I can, this story both perplexed me and intrigued me.

How on earth can we be running out of sand? I knew then that this was the environmental and humanitarian topic I wanted to raise awareness of.

It seems the boom in demand for sand in industries such as construction and beach re-nourishment are the main culprits – the sand we need for the way we live our lives today cannot replenish itself fast enough.

That seems impossible for such a ubiquitous material. But only rough-edged ocean and riverbed sand can be used for these purposes; desert sand is simply too smooth. Dubai has to import sand from Australia.

It also seems unimaginable that this has also led to a growth in sand mafias, and that people have lost their homes, livelihoods and even their lives.

I made this camera-less series along the shoreline of my local beach. The vivid images are produced with sand, seawater, sunlight and digital manipulation.

Using expired black and white photo paper and exposures varying from 15 minutes to a few hours, I bury the paper in sand. I may then excavate the sand, make marks or allow the surroundings to influence the outcome.

Rather than using photographic fixer, the exposed sheets are scanned before they are sealed in a light-tight box.

The final images are then produced with a simple but particular digital process to determine the final colours.

I have been bewitched by the Celestographs of August Strindberg and I feel Harena Now, created along similar lines, ricochets between a sense of the microscopic to the vastness of space; from the tiniest grain of sand our civilisation as we know it has grown.

Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin’s comment on the Afghan war through their collaboration The Day Nobody Died also has synergy.

Rather than confronting viewers with hardcore examples of the effects of crisis, I wanted to lure people in by creating work that would be visually eye-catching; something that would make people stop and ask, “What’s that?”.

I’m interested in how non-documentary images can be used to spark conversations but also how, or if, it can provoke action as perhaps a more photo-journalistic image might.

By not doing what is expected, as Broomberg and Chanarin did, I hope the work will provide another way for viewers to consider the human impact on our world. I do not want people to be turned off by what they see, to not be able to face something in a world that can at times seem overwhelmed with calls for help and/or action.

Harena Now also plays with ideas of control and a lack of. Trying to control the black market for sand, and even the legal demand for sand is something that is proving a challenge. The very nature of how Harena Now is created involves an element of relinquishing control while also implementing it.

It is also important to me that I also minimise my own photographic impact on the environment. By reducing or omitting photographic chemicals, and working outdoors in ways that have no detrimental effect seems the right way for me to make my work.

In the long-term, I hope to work with selected organisations working on the sand crisis to use Harena Now as a tool within international discussions.

Harena is the Latin word for sand. It also symbolises an arena/place of contest.

As the developing environmental/humanitarian issues surrounding our use of sand could be described as a battle, for those trying to survive and make a living, for the wildlife and habitats caught up in the process, for those trying to determine a solution, it is apt that Harena signifies the material (sand) and implies conflict.

One of my earliest influences was geologist Michael Welland. His passion for this natural resource was infectious. He described it as the “unsung hero” of our lives and the lives of other creatures – “without it life as we know it would not exist”.

© Josie Purcell

© Josie Purcell

© Josie Purcell

© Josie Purcell

© Josie Purcell

© Josie Purcell

© Josie Purcell

Not a Shutter Hub member yet? Join here for opportunities to promote your work online and in exhibitions, access selected opportunities, events, seminars and workshops, meet up and share photographic experiences, and become part of our growing community…